Welwyn Garden City is a brave attempt to create a Utopia – an ideal community. The word was coined by Sir Thomas More in his political satire of the same name published after his death in 1515. It is derived from Greek, literally good-place or no-place – ie impossible ideal.

In Victorian times several successful industrialists sought to build utopian model villages for their workers, inspired by a combination of religious conviction, guilt, paternalism, and self-interest. The two best known were Port Sunlight on Merseyside and Bournville near Birmingham.

Port Sunlight was founded in 1890 by William Lever, later Lord Lever, for his employees manufacturing Sunlight Soap, which he had made famous by clever advertising. He created a beautiful and comfortable estate, which combined visual appeal and social purpose.

Bournville’s creators were the Quaker brothers George and Richard Cadbury, who started building in 1898. Their father John was a teetotaller who had built up a thriving business in drinking cocoa, motivated by a desire to provide a healthy alternative to alcohol which he saw as a major source of social problems. Gin shops were popular, promising ‘Drunk for a penny, Dead drunk for two pence’. John believed that the man who abstained from alcohol could afford a joint of beef on a Sunday. Naturally no pubs were allowed in Bournville.

Interestingly, William Lever had a similar view of alcohol. His parents were strictly observant Congregationalists; his father James was a teetotaller and a non-smoker, who applied his religious principles in his business life as well as in his personal life. William too was a life-long teetotaller.

He ran Port Sunlight on paternalistic lines and workers who lost their jobs could be almost simultaneously evicted. On the other hand, he was keen to allow the residents of Port Sunlight a degree of democratic control. In 1900 he opened the Bridge Inn which of course sold no alcohol. Within two years the workers became restive and sought to change its status to a licensed house. Lever announced that he would not impose his own views, and that the issue would be decided by a referendum; insisting somewhat unconventionally for that time that women would take part. However, he stipulated that the Bridge would only become a true British pub if a supermajority of 75% was in favour. (Very sensible – only a rash person would hold a referendum on a major issue without requiring a substantial majority in favour). He probably felt confident that the outcome would support his abstemious sentiments, but in the event more than 80% voted for an alcohol licence.

the The World’s End is an apocalyptic science fiction comedy film from 2015. It tells the story of five middle-aged men on a nostalgic pub crawl which gets disrupted when they discover that the locals have been taken over by aliens. Their aim had been to visit twelve pubs, finishing at one called The World’s End. The film was shot in Letchworth, Welwyn Garden City, and for internal scenes Elstree Studios. The lead actor and writer, Simon Pegg, lives in Essendon and said that he chose the two Garden Cities as examples of pleasant modern towns. He must have been aware of the reputation of Letchworth as being a mostly dry town with few pubs but perhaps this was all part of the joke. To make up numbers some buildings including Letchworth Station had to be dressed up as pubs.

Ebenezer Howard devoted a section of his book Garden Cities of Tomorrow to Temperance Reform. He was not keen on alcohol but did not favour banning it completely, instead suggesting that profits from its sale should be diverted to building “asylums for those affected by alcoholism”. He proposed that the provision of services such as pubs should be decided by public ballot.

The early settlers in Letchworth (which included Howard) were idealists seeking Utopia and far from conventional. George Orwell somewhat sweepingly described the new town as attracting every form of “crank: fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature-Cure’ quack, pacifist, and feminist”. (Road to Wigan Pier, p 152).

When an enlightened ballot was set up to decide the provision of pubs, in which both men and women took part, a small majority voted against. Women carried the day, perhaps because they did not like to see men drunk. Letchworth was a dry town until 1960 with just one inn, The Skittles, set up in 1907. This sold only soft drinks and so was the legendary pub without beer; it was soon also without skittles as the locals shunned the game.

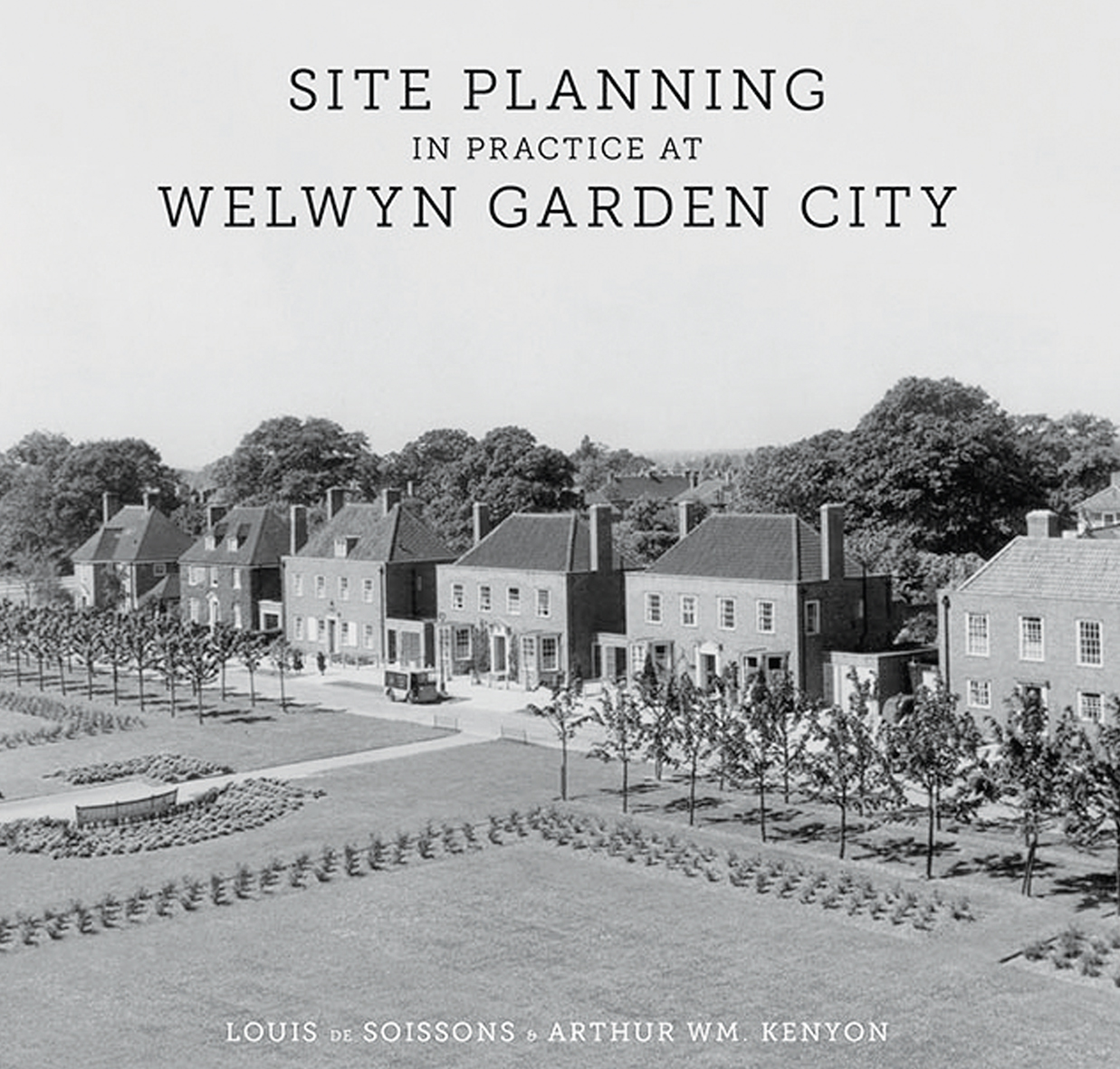

The Directors of the Company building Welwyn Garden were keen to avoid the cranky image of Letchworth, while maintaining its noble objectives. So, a “wet restaurant” was set up called The Cherry Tree. It was a modest wooden structure, designed by Louis de Soissons in 1921, Licenced in 1922. A larger public house replaced it in 1932, which was demolished in 1991. The facade was retained for the Waitrose supermarket now occupying the site.

There already were pubs in the area. The Beehive in the small village of Hatfield Hyde dated from the early 17th Century, although it was only given a Licence in 1842. Owned by Lord Salisbury it became a favourite destination for early Garden citizens to walk to across the fields on a nice summer evening. Once the QEII hospital opened it was popular with hospital staff. It closed in 2016 as it was losing money and now looks very sad and empty.

The non-conformist spirit was certainly strong in Welwyn Garden. The Welwyn Times for 21/9/23 reports that, following an enquiry from the WGC Church Council, the Parish Council after a lively discussion agreed to ask the WGC Company to prohibit "calling" bells or other continuous ringing. There followed a number of letters in the paper; one favoured a ban to " prevent a small minority disturbing the tranquillity or recreation of the vast majority. Continuous bell ringing on a Sunday is anti-social and intolerable to enlightened communities". Eventually all the churches in the area agreed not to ring their bells, which is still generally the position today.

The provision of pubs in the centre of the town remains a sensitive matter. Wetherspoons bought one of the large houses on Parkway, near the Fountain, some years ago and sought a Licence for a pub to be called the Cherry Tree. This was hotly contested by locals, ostensibly as being in the wrong location but more probably as being the wrong sort of pub. Planning permission was refused twice and in 2021 Wetherspoons threw in the bar towel and put the building up for sale. As this newspaper reports on 5th April, the building is now to be a Nursery School – so no danger of underage drinking.