Welwyn Garden City Heritage Trust continues its look back at the history of the second garden city. This week it's the Hertford and Luton branch lines through the town.

Great technical breakthroughs have made some people rich but others poor. Good examples are the dot.com revolution and cryptocurrencies.

In Victorian times it was the railways. In 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened; it was the world's first inter-city passenger railway with scheduled services. There soon followed a rush of applications to build lines. Each required an Act of Parliament, but this was easy to obtain as the Government did not vet applications. All it needed was a supportive MP and speculative investors. Railway mania broke out in the 1840s with the price of railway company shares rocketing then collapsing.The mania peaked in 1846, when 263 Acts of Parliament were passed approving new railway companies.

About a third of the railways authorised were never built the companies either collapsed, or were bought out by larger competitors, or turned out to be fraudulent enterprises. The lines around Welwyn were typical of these speculative efforts. The Great Northern Railway was set up in 1846 to connect London and York. It quickly saw that seizing control of territory was key, and acquired many local railways along its route, whether actually built or not.

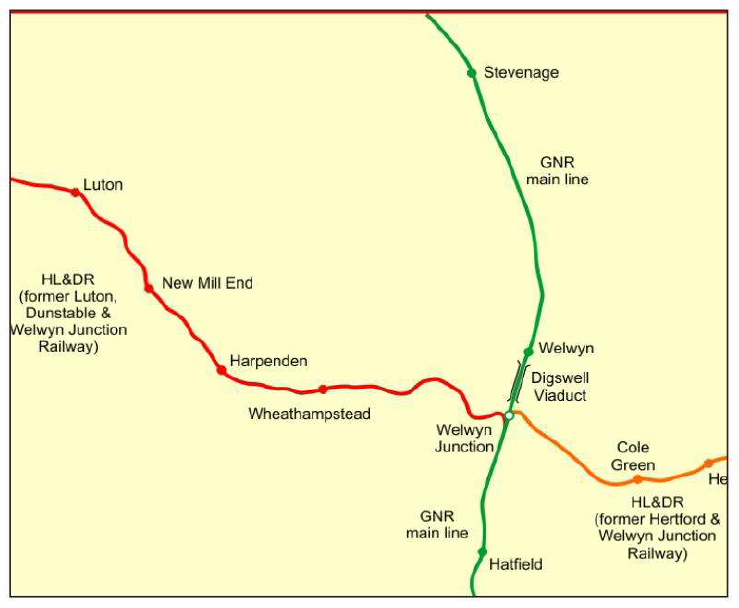

Above: A map of the Hertford, Luton & Dunstable Railway. Picture: Afterbrunel, Creative Commons.

The Hertford & Welwyn Junction Railway was authorised in 1854, to boost the fortunes of Hertford by linking it to the GNR. The plan was to merge with it at Digswell, via spurs running both north and south. A similar initiative by the burghers of Luton led to the Luton, Dunstable and Welwyn Junction Railway in 1855. This also envisaged joining the GNR at Digswell via similar spurs, plus a bridge over the main line connecting to the Hertford line directly. These two lines were both under financial pressure and amalgamated in an Act of 1858, to form the Hertford, Luton and Dunstable Railway (see map). This was itself swallowed up in 1861 by the GNR, which scrapped the plans to build a bridge and the northbound spurs. Thus, Hatfield became an important junction acting as a terminus for both these branch lines as well as another from St Albans.

After Ebenezer Howard set about creating Welwyn Garden in 1920, a Halt was built on the Luton branch just before it joined the main line. This was important for builders and commuters because special trains ran directly from there to King's Cross a few times a day. It was only a stop gap and made redundant when Welwyn Garden station was opened in 1926, 200 yards to the south of the Halt. It was by then run by the LNER (London and North Eastern Railway), a grouping of railways including the GNR formed in 1923.

Above: The Welwyn Garden City Halt in the early 1920s. Picture: Disused Stations - http://disused-stations.org.uk/

The Luton branch line was well used. Goods trains took gravel from a pit near Wheathampstead and subsequently filled it with rubbish from London. Nurseries were served by daily deliveries of manure from London Zoo. Passengers included playwright George Bernard Shaw travelling from his house in Ayot St Lawrence. The Hertford branch was important too because sidings were constructed off it to serve the new industries on the east side of the town. Goods trains could run from there to the London docks via a link at Hertford.

After serving the town well, these single lines lost traffic to road transport and were closed to through traffic in the mid-1960s. Today parts of both have been converted to attractive level paths for walkers and cyclists. The Luton one - the Ayot Greenway - runs for three miles from the White Bridge.

Above: A view of Cole Green Station, demolished c1975. Picture: David Hillas, Creative Commons.

The Hertford one - the Cole Green Way - runs for six and a half miles, starting from Cole Green Lane. They still serve the town although in ways that would surprise the Victorian speculators who built them.

First published in the Welwyn Hatfield Times on 28 December 2022.